More than 3,500 status Indian volunteers enlisted in the first World War from all across Canada. According to Indian Affairs records this “number represents approximately thirty-five per cent of the Indian male population of military age” between 1914 and 1919, and this doesn’t even include the enlisted men that Indian Affairs didn’t know about.1 The Great War broke out in 1914 many years before our people were granted Canadian citizenship.2 At that time we couldn’t vote in the federal or provincial elections and had few rights that Canadian citizens had. But when England declared war on Germany in August of 1914 the call for volunteers came and large numbers of Treaty and status Indian men from across the country volunteered and gave their lives on the front lines in Europe.

The Canadian government did not expect so many of our people to volunteer for the war and initially wouldn’t permit our men to serve overseas. Indian Affairs claimed they did this to protect us because “the enemy considered Natives to be ‘savage’” and they feared that “this stereotyped view would result in the inhumane treatment of any Aboriginal people who were taken prisoner.” But many Indian men slipped through that rule because the policy was not strictly followed. Then when cries from the Allied Forces called for more troops Canada reversed this policy in late 1915.3

In training and overseas on the front lines our men proved their worth. For those who were raised in the bush hunting and trapping, their skills at scouting and marksmanship were highly prized. A good hunter has a lot of self-discipline, patience, skills, and the physical endurance. Some of the First Nation soldiers endured culture shock when they shipped off for training and hit the front lines in Europe. Many from the north had never been out of the bush before or spent much time around non-Indian people. But the young men who went to residential school were familiar with the military life style and didn’t have as much trouble adjusting to the drills and military discipline.

In training and overseas on the front lines our men proved their worth. For those who were raised in the bush hunting and trapping, their skills at scouting and marksmanship were highly prized. A good hunter has a lot of self-discipline, patience, skills, and the physical endurance. Some of the First Nation soldiers endured culture shock when they shipped off for training and hit the front lines in Europe. Many from the north had never been out of the bush before or spent much time around non-Indian people. But the young men who went to residential school were familiar with the military life style and didn’t have as much trouble adjusting to the drills and military discipline.

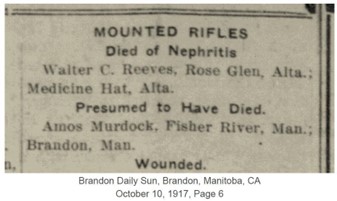

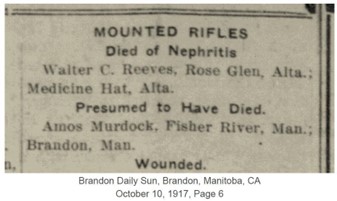

In World War I we lost three young men from Fisher River overseas: Amos Murdock (1896- 1916), John George Sinclair (1891-1917), and McIvor Sinclair (1892-1917). Amos was born in Norway House, the son of Peter and Ellen Murdock. Peter Murdock brought his homestead land at Gold Eye Lake into the reserve when he joined Fisher River through Treaty Adhesion in 1908. Amos served in the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifles, Saskatchewan Regiment, and lost his life during one of the

Battles of the Somme.4 The Battle of the Somme raged from July to November 1916. It began early morning on July 1st near the towns of Hamel and Beaumont with thousands of British and Newfoundland soldiers striking towards the German line. History tells us that in less than thirty minutes that first battle was over and 57,470 British soldiers were killed. On the morning of September 15th, the Canadian forces moved in to capture a refinery and two trenches from the Germans. The Canadian troops won the day but Private Amos Murdock didn’t make it.5 He was reported wounded and missing after the battle, then reported presumed dead. They buried him at Vimy Memorial cemetery in Pas de Calais, France.6 Christina Cochrane (nee Murdock) remembered stories about her uncle Amos Murdock going to war. Peter and Helen Murdock were her grandparents and she was raised up by them. Amos attended Brandon industrial school, went to war, and never came home.

Private McIvor Sinclair, son of John and Nancy Sinclair, passed away a few months after Amos on November 8, 1916.7 Like Amos, McIvor was a Private in the Canadian Mounted Rifles, Saskatchewan Regiment, and lost his life during the Battle on the Somme. McIvor left behind his widow, Edith Sinclair, who left the community a year later and eventually moved to Selkirk. McIvor Sinclair is buried at the Lovez Military Cemetery in Pas de Calais, France.8 A few months later, on April 5, 1917, McIvor’s older brother Private John George Sinclair died in action. John George was in the Canadian Infantry, Manitoba Regiment, and is buried at the Ecoivres Military Cemetery, also in Pas de Calais, France.9 John and Nancy Sinclair lost two sons in WWI.

In World War I most of the First Nation soldiers served as scouts and snipers but in the second World War they served in a wide range of roles in the army, navy and air force, and they saw action in all the Canadian operations overseas including: Hong Kong, December 1941; Dieppe, August 1942; Sicily, 1943; Italy, 1943 to 1945; and North-West Europe in 1944 to 1945.10

Most of our WW II soldiers enlisted from the reserve here. Others enlisted from Brandon residential school and a few were living in Winnipeg and enlisted from there. There was a big recruitment campaign during World War II for First Nation and Métis volunteers.

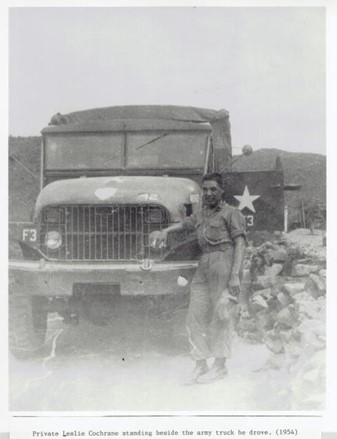

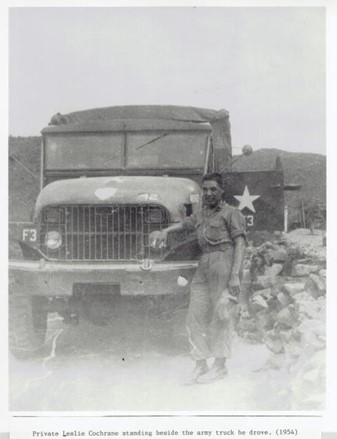

Leslie Cochrane joined the army in May of 1943 in Winnipeg when he was 17 years old. He took basic training at Fort Garry, then advanced training in Shilo, then was sent overseas for more training in Liverpool, England. From there he was shipped to the front lines in Italy. Leslie recalls sailing in the Mediterranean Sea where the ships were being air raided by the Germans. After 18 months of action Leslie was wounded and went totally deaf. A shell exploded right beside him and rendered him unconscious

Leslie Cochrane joined the army in May of 1943 in Winnipeg when he was 17 years old. He took basic training at Fort Garry, then advanced training in Shilo, then was sent overseas for more training in Liverpool, England. From there he was shipped to the front lines in Italy. Leslie recalls sailing in the Mediterranean Sea where the ships were being air raided by the Germans. After 18 months of action Leslie was wounded and went totally deaf. A shell exploded right beside him and rendered him unconscious

and spent two months in hospital. Still suffering from deafness he worked in the mobile laundry for a few months then returned to active duty and was shipped to Holland. When his hearing returned suddenly, he said it was the happiest day in his life. Leslie was discharged in 1946. He came home and got married in 1951, then in June of 1953 he re-enlisted. After a few months training in Petawawa, Ontario, he was shipped to Korea and finished his term in June 1956. Then again in October 1961 he rejoined the Winnipeg Rifles and went for training at Minto Armories in Winnipeg. Leslie retired from the military and returned home to Fisher River. Later in life he told us he tried to get veterans benefits like the white veterans received but was denied, and was told he would only get land if he got out of treaty. He also said the army was a picnic compared to residential school at Brandon.

Walter (Waldy) Hudson enlisted in Winnipeg in September 1942 when he was 18 years old, without telling his family of his intentions. He did basic training in Portage la Prairie for a few months then advanced training in Brandon. From there he shipped out to Liverpool, England, for advanced training, then was sent to France as a Gunner. Waldy remembers the war vividly. He recalls hitting the beaches in July of 1942 and being in heavy battle, day and night, four to five days strait at a time. He served for two years until he was wounded in Holland. A mortar barrel fell into the trench, two of his comrades were killed and he was severely wounded. He received surgery on his wounded leg and was kept in the

Veteran’s Hospital in France then to a hospital in England, then shipped home and spent three months at Deer Lodge Hospital in 1945. While in the hospital he came across some of his friends and relatives. His parents sent him gifts while he was overseas and his brothers wrote him letters. Waldy told us that he never really had a chance to feel lonely for his family because he was too busy. When he did think about home and family, he said he never thought he would make it home because he was too far away. He didn’t bring home any souvenirs from the war either, “everything was blown to hell,” he told us, he “was lucky to bring himself back.”

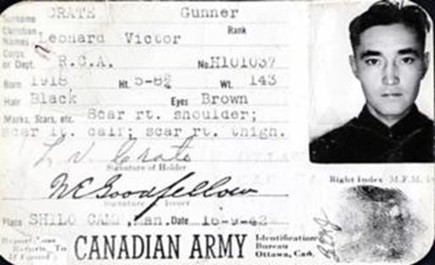

We lost a few good men in World War II. Three of them were Rifleman George Alexander Cochrane (1920-1945), Gunner Arthur Murdock (1919-1945) and Bombardier Leonard Crate (1918-1945). Leonard Crate and Arthur Murdock are listed in the World War II, Roll of Honours list, killed in action, and both are buried at the Koostatak United Church Cemetary. Not much is known of their wartime experiences. We do know that Leonard Crate passed away when he was stationed at Brandon, Manitoba, when the army vehicle he was in crashed with a freight train in Douglas, Manitoba, in January 1945.5

We lost a few good men in World War II. Three of them were Rifleman George Alexander Cochrane (1920-1945), Gunner Arthur Murdock (1919-1945) and Bombardier Leonard Crate (1918-1945). Leonard Crate and Arthur Murdock are listed in the World War II, Roll of Honours list, killed in action, and both are buried at the Koostatak United Church Cemetary. Not much is known of their wartime experiences. We do know that Leonard Crate passed away when he was stationed at Brandon, Manitoba, when the army vehicle he was in crashed with a freight train in Douglas, Manitoba, in January 1945.5

A few men signed up during the Korea War also like Leslie Cochrane and Harvey Crate. Harvey joined the army in April 1952 and served in Korea and Japan. He returned home in late 1953 then transferred to the Airborne Unit, 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, and was stationed in London, Ontario. He received an honorable discharge in 1955 and returned home.

The last surviving member of our community who saw active service is Sargent John Silver who served in the United States Army. John Silver was born Glen Harold Bowers, the son of Suzy Bowers, and was part of the 60s Scoop. Glen was adopted to the Silver family in Kentucky where he grew up and joined the USArmed Forces. Welcome home Sargent Silver. We look forward to hearing more about you and your time in the service.

Fisher River Cree Nation is proud of all our veterans. In time we hope to document all their accomplishments and contributions.

Fisher River Cree Nation is proud of all our veterans. In time we hope to document all their accomplishments and contributions.

Lest We Forget—Remembering With Respect and Honour

Winona Wheeler & Russell Kirkness November 2023

1 Duncan Campbell Scott, “The Canadian Indians and the Great World War,” Guarding the Channel Ports, vol. 3 of Canada in the Great War (Toronto: 1919), 1.

2 Canada, Veterans Affairs, Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields (Ottawa: Veterans Affairs Branch, 1993), 5.

3 Canada, Native Soldiers, 6.

4 Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 103; Veterans Affairs Canada, “Canadian War Memorials—In Memory of Private Amos Murdock,” http://www.vac- acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=collections/virtualmem/Detail&casualty=1572246;

5 Veterans Affairs Canada, “Canada Remembers—The Battle of the Somme,” http://www.vac- acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=feature/bh_somme2006/bhsomme_info

6 Veterans Affairs Canada, “Canada Remembers—The Battle of the Somme,” http://www.vac- acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=feature/bh_somme2006/bhsomme_info;

7 Veterans Affairs Canada, “Canadian War Memorials—In Memory of Private McIvor Sinclair,”

http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=collections/virtualmem/Detail&casualty=29565; 8 NAC, RG10 Black Series, vols. 9353-9403, Treaty Annuity Paysheets, June 22-23, 1917, Fisher River Band, #202 John Sinclair note “son killed in action” fo. 2; Ibid., June 21-22, 1918, #344 Mrs. McIvor

Sinclair (no children), Fo. 5; Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 106.

9 NAC, RG10 Black Series, vols. 9353-9403, Treaty Annuity Paysheet, June 22-23, 1917, #202 John Sinclair, “one son killed in action,” fo. 2; Veterans Affairs Canada, “Canadian War Memorials—In Memory of John George Sinclair,” https://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/canadian-virtual-war-

memorial/detail/66092

10 Gaffen, Forgotten Soldiers, 80, 40.

In training and overseas on the front lines our men proved their worth. For those who were raised in the bush hunting and trapping, their skills at scouting and marksmanship were highly prized. A good hunter has a lot of self-discipline, patience, skills, and the physical endurance. Some of the First Nation soldiers endured culture shock when they shipped off for training and hit the front lines in Europe. Many from the north had never been out of the bush before or spent much time around non-Indian people. But the young men who went to residential school were familiar with the military life style and didn’t have as much trouble adjusting to the drills and military discipline.

In training and overseas on the front lines our men proved their worth. For those who were raised in the bush hunting and trapping, their skills at scouting and marksmanship were highly prized. A good hunter has a lot of self-discipline, patience, skills, and the physical endurance. Some of the First Nation soldiers endured culture shock when they shipped off for training and hit the front lines in Europe. Many from the north had never been out of the bush before or spent much time around non-Indian people. But the young men who went to residential school were familiar with the military life style and didn’t have as much trouble adjusting to the drills and military discipline. Leslie Cochrane joined the army in May of 1943 in Winnipeg when he was 17 years old. He took basic training at Fort Garry, then advanced training in Shilo, then was sent overseas for more training in Liverpool, England. From there he was shipped to the front lines in Italy. Leslie recalls sailing in the Mediterranean Sea where the ships were being air raided by the Germans. After 18 months of action Leslie was wounded and went totally deaf. A shell exploded right beside him and rendered him unconscious

Leslie Cochrane joined the army in May of 1943 in Winnipeg when he was 17 years old. He took basic training at Fort Garry, then advanced training in Shilo, then was sent overseas for more training in Liverpool, England. From there he was shipped to the front lines in Italy. Leslie recalls sailing in the Mediterranean Sea where the ships were being air raided by the Germans. After 18 months of action Leslie was wounded and went totally deaf. A shell exploded right beside him and rendered him unconscious

Fisher River Cree Nation is proud of all our veterans. In time we hope to document all their accomplishments and contributions.

Fisher River Cree Nation is proud of all our veterans. In time we hope to document all their accomplishments and contributions.